Kiobel Oral Argument: Piracy May Spell Trouble for Shell

October 3, 2012 Leave a comment

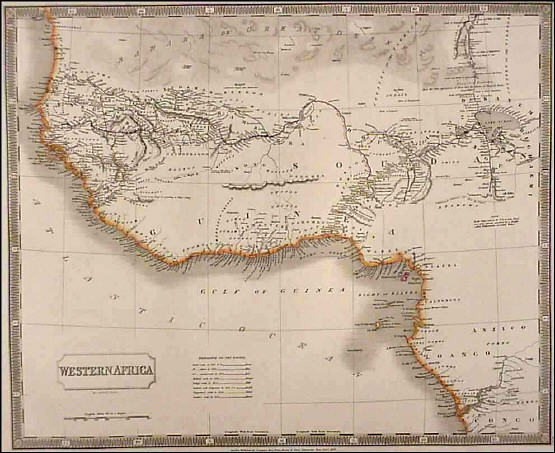

The Supreme Court opened up its October term with a healthy dose of international law in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Shell. The petitioner, Esther Kiobel, is bringing suit against Royal Dutch Shell (Shell) alleging that the oil company aided and abetted the Nigerian government in committing gross human rights violations in the oil rich Ogoni region of Nigeria.

This is the second time this year that the Court has heard Paul Hoffman’s arguments in favor of the plaintiffs and Kathleen Sullivan’s arguments on behalf of Shell, and maritime piracy played a role in both rounds of arguments.

The first round of Kiobel oral arguments considered whether the Alien Tort Statute (ATS) could be applied to corporations as well as natural persons. There, Justice Breyer evoked the concept of “Pirates, Incorporated” to inquire into whether an in rem action against an 18th century pirate could be foreclosed because “Pirates, Inc.” rather than the individual pirate, owned the property at issue.

In the second round of oral arguments, held yesterday morning, the issue had changed from whether the ATS can be applied to corporations to whether it can be applied extraterritorially. Despite this change of focus, maritime piracy played an even more important substantive role in the second iteration of the Kiobel arguments than the first.

Piracy first came up when Justice Scalia asked Royal Dutch Shell’s attorney, Kathleen Sullivan, whether she believed – as Scalia thought she “must” – that the ATS applied to high seas conduct. She did not. Ms. Sullivan then quickly tried to turn her argument to the Marbois incident concerning an assault on a French diplomat.

But Chief Justice Roberts immediately raised the question of piracy again, noting that “it was the most clear violation of an international norm” at the time of the ATS’s passage.

Ms. Sullivan again attempted to minimize her high seas argument, noting that even if the justices concluded that the ATS reached high seas conduct, it does not extend into the territory of another state. However, she doubled down when she argued that Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain – the last ATS case heard by the Supreme Court – does not foreclose the possibility that the ATS’s reach stops at the high seas, as that opinion stated that piracy might be an area covered by the statute.

Despite her repeated attempts to stray away the issue of piracy, the oldest international crime came up again and again, including in the context of Filartiga v. Peña-Irala, where the Second Circuit held that, “[f]or the purposes of civil liability, the torturer has become – like the pirate and slave trader before him – an enemy of all mankind.”

As Shell’s attorney, Ms. Sullivan wished to steer clear of the issue of maritime piracy for several reasons. The first is that the Supreme Court explicitly found that the First Congress meant to include piracy as one of three torts available to 18th century ATS plaintiffs. The Supreme Court would likely be reluctant to admit that it was wrong less than a decade after Sosa was handed down.

Second, foreclosing ATS claims that occur on the high seas is the furthest possible extension of the respondents’ argument, one that the majority need not adopt to reach the respondents’ desired verdict.

Finally – and this may have been what Justice Scalia was getting at when he initially posed the question – it is difficult to find an example of an American law that applies on the high seas but not on foreign soil.[1] The presumption against extraterritoriality is purely a creature of Congressional intent, and it seems that Congress rarely distinguishes between the high seas and foreign soil when considering a statute’s extraterritoriality.

If the conservatives on the Supreme Court find the argument that ATS application on the high seas and on another country’s soil rises and falls together persuasive, there is enough historical evidence that the ATS was meant to apply to piracy that more newly-minted universal violations could ride on piracy’s coattails and allow for extraterritorial application of the ATS.

The effect such an opinion would have on pending litigation over a high seas requirement for facilitators of piracy is better saved for another day.

[1] Depending on the ultimate outcome of pending litigation, a notable exception to this general rule could be, however ironically, 18 USC § 1651, the statute criminalizing piracy.