Pirates in Prada and Proving it

February 3, 2011 Leave a comment

The Economist has a comprehensive report touching on many of the practical issues created by the rise of Piracy in the Indian Ocean. In the conclusion to the report, the report explains some of the reasons why there have not been more comprehensive efforts to address the problem.

Unfortunately, too many people like things as they are. Pirates gain wealth, excitement and glamour. Marine insurers, which last month extended the sea area deemed to be at threat from Somali pirates, are making good money from the business that piracy generates. At least for the time being, shipowners are willing to take the calculated risk of sailing in pirate-infested waters; so long as everyone bears his part of the extra $600m a year in premiums, they can pass the bill on to their customers. Patrolling foreign navies can demonstrate their usefulness to their sometimes sceptical political masters, while countries such as China and Russia are strengthening their operational experience.

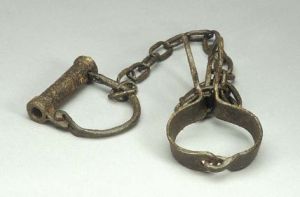

On another issue, the report acknowledged the difficulty in compiling evidence to prove acts of piracy. Professor Eugene Kontorovich has advocated for “Equipment Articles,” taking a cue from the slave era in which the British enacted laws creating a presumption that ships were engaged in slavery if they were in possession of certain equipment such as shackles. In the context of piracy, Professor Kontorovich states:

Equipment Articles could create a presumption of piracy for people found on a vessel less than a certain length, with engines of a certain horsepower, equipped with grappling hooks, boarding ladders, armed with RPGs and/or heavy machine guns, and/or far out at sea with obviously inadequate stores of food and water (which could suggest the skiff operates from a mothership).

Boarding ladders, such as the one seen in the header to this blog, and grappling hooks permit pirates to quickly gain access to a ship. But, the practical problem with this suggestion is set forth in the Economist report: “If they are caught in the middle of an attack, the pirates have no hesitation throwing their weapons—typically AK47 machine guns and rocket-propelled-grenade launchers—and their scaling ladders overboard to destroy evidence of their intentions.” All that would be left is a skiff with a large engine and, if the pirates are clever, a fishing net. The Equipment Articles would be of questionable utility in such circumstances.

But there is also a due process problem with such laws. International criminal law has adopted the beyond a reasonable doubt standard of proof. Equipment Articles appear to lower the burden of proof such that the prosecution of a pirate would only require prima facie evidence that a suspect intended to commit piracy. In other words, Equipment Articles put the onus on the suspect to disprove that they intended to engage in piracy. Alternatively, Professor Kontorovich notes that during the slavery era, the United States never enacted Equipment Articles, but instead considered the possession of equipment as circumstantial evidence of slavery. This latter use is more consonant with contemporary International Criminal Law practice. Short of catching Pirates as they attempt to board a ship or after they have already taken hostages, compiling sufficient evidence to prove piracy will continue to pose a problem.

UPDATE: The Danish Navy was forced to release six suspected pirates for lack of proof to sustain a conviction. “The pirates “had thrown all their equipment used for piracy into the sea before the boat crew members of the Esbern Snare [the Danish Naval ship] had boarded. “