February 16, 2012

by Shannon Maree Torrens

The economic cost of piracy has joined the already substantial political and security concerns of such operations, as an issue requiring further research and consideration by the relevant stakeholders. In this vein, the Colorado-based One Earth Future Foundation, which studies the effects of piracy through the Oceans Beyond Piracy project, has released its 2011 working paper on The Economic Cost of Somali Piracy. In order to ensure reliability, the report builds on dialogue and feedback from Oceans Beyond Piracy’s 2010 assessment of the cost of piracy with data obtained through collaboration with maritime stakeholders from industry, government and civil society, in addition to commentators and experts in the field. As the second report of its kind, the paper aspires to flag pertinent concerns for the Oceans Beyond Piracy Working Group, which will release recommendations for a more coordinated, and comprehensive strategy against piracy in July 2012.

In highlighting its concerns about the economic cost of Somali piracy to relevant stakeholders and the wider community, the report estimates the 2011 economic cost of piracy to be $6.6 – $6.9 billion US dollars. The majority of which is spent in mitigation of piracy attacks rather than in ransoms, as is most commonly believed and also portrayed by the media. The report only calculates direct costs, as indirect figures were too difficult for the research to quantify and in doing so assesses nine different cost factors specifically focused on the economic impact of Somali piracy. Namely: increased speeds, military costs, security guards and equipment, re-routing, insurance, labour, ransoms, prosecutions and imprisonment and counter-piracy organisations. The report subsequently found that 80% of all costs relating to countering piracy attacks are covered by the shipping industry, while governments finance the remaining 20% of the expenditures. The approximately $7 billion figure for 2011, is down from the $7 – $12 billion that was estimated in the 2010 report. While the 2010 estimate was higher, the 2011 report is said to be based on more authoritative and exact information according to the author of the report Anna Bowden who explained that in reality the figures of 2010 and 2011 are likely to be similar.

Key piracy developments: overview

The report outlines what it believes to be the key piracy developments affecting the cost of piracy in 2011, where there was an increase in attacks by Somali pirates, particularly in the first quarter. There was a record of 237 piracy attacks, rising from the 212 in 2010. However the proportion of successful attacks fell, with only 28 of the vessels actually captured, in comparison to the 44 in 2010. This is most likely due to the use of private armed guards on vessels and naval operations that have become more familiar dealing with piracy issues. The report recognised that 99% of the $7 billion was spent on yearly recurring costs associated with the protection of vessels including $2.7 billion in fuel costs, $1.3 billion for military operations and $1.1 billion for security equipment and armed guards.

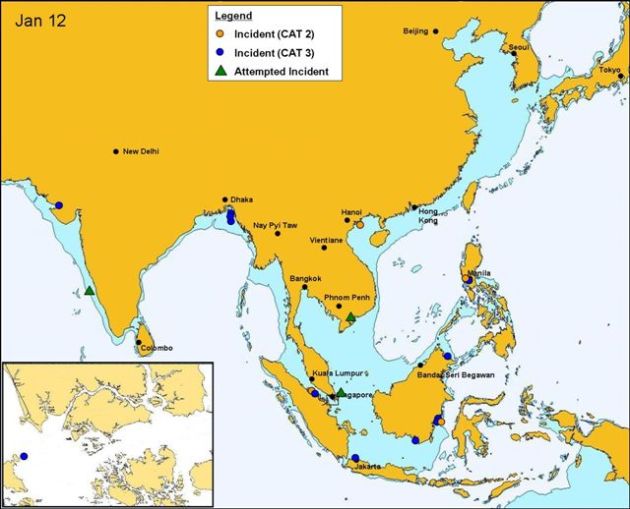

In other observations, shipping behaviour altered whereby shippers increased payments necessary to harden vessels, hire private security and increase speed in high risk areas. Further, the geographic expansion of pirate activities increased eastwards towards India, and northeast towards the Gulf of Oman and Strait of Hormuz. New trends in piracy mitigation included the rerouting of ships so that they transited close to the western Indian coastline rather than the Cape of Good Hope. As will be discussed below, only $16.4 million was spent on prosecutions and $160 million was collected by pirates in the form of ransoms, which is only 2% of the overall economic expenditure. These figures represent a disproportionately small contribution to the economic cost of piracy compared to the $7 billion spent in order to stop the attacks.

Further key developments surrounded ransoms, which increased from $4 – $5 million, as did the duration that ships were held hostage during negotiations. Meanwhile, the human cost in the loss of lives cannot be adequately quantified, but notably increased from eight in 2009 to 24 in 2011, despite the significant economic effort to avoid the attacks. 2011 evidenced an increase in seafarer deaths, in addition to specific incidents highlighted in the media where groups of pirates were accused of kidnapping tourists and humanitarian workers on land in Somalia and Kenya. This resulted in a more aggressive response from military forces conducting counter-piracy missions in the region while pirates changed their primary operations from large vessels to smaller fishing boats.

Piracy and prosecutions

An issue of particular interest is the comparatively low cost of prosecutions, imprisonment and local legal capacity building, which at $16.4 million is a relatively small proportion of the $7 billion overall economic cost of piracy. This figure is an estimate of the cost of trials and imprisonment in the four selected regions of Africa, Europe, North America and Asia. The report highlights that in attempting to find a legal resolution to the issue of piracy, in October 2011, the United Nations Security Council called on UN member states to criminalise piracy, asking member states to report to the Secretary General on the measures they have taken to criminalise piracy.

Certain countries such as the United States and Oman have sentenced pirates to life imprisonment, with South Korea sentencing one pirate to death for murder. In estimating the cost of prosecutions in 2011, the report calculated the average cost of pirate trials that were conducted, in addition to the cost of imprisonment for suspected Somali pirates during the year, accordance with economic development and prosecutorial costs. The cost of trials and imprisonment in Kenya and the Seychelles were not included, due to the fact that the relevant costs for these prosecutions are covered by funding from the UNODC Counter Piracy Programme and other international funding mechanisms.

According to a report released in 2011 by Jack Lang, the United Nations Secretary General’s Special Adviser on Legal Issues Relating to Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, more than 90 per cent of captured pirates will be released without prosecution. The report notes that over the previous few years 1,089 pirate suspects had been arrested for piracy and those individuals have either been tried or are awaiting trial in 20 countries, a figure which has risen from 10 countries in 2010. Lang therefore proposed a specialised extraterritorial Somali court system with its seat in Arusha, Tanzania based on an estimated cost of $2.73 and $2.33 for each following year.

In consideration of this, and as already discussed in this blog, criticisms as to the resources needed for a fully internationalised piracy tribunal, that may cost up to an estimated $100 million, are short sighted against the report’s figure of $7 billion for the overall cost of piracy. In an earlier post by Matteo Crippa, we indicated that the most relevant issue in evaluating the effectiveness of international prosecution was its real deterrent effect. In comparison to an overall figure of $7 billion, $100 million for an international tribunal, however costly in isolation is comparatively low. These disparate figures might also justify a substantial increase in funding for the current localised prosecutorial initiatives, which are similarly capable of meeting effective deterred goals. Whatever solution is chosen, it is clear that prosecutions have not been prioritised as a budgetary matter.

Conclusions

The 2010 Oceans Beyond Piracy report was widely referred to in piracy commentary. The updated and more accurate 2011 version has already been critiqued by various sources. When considering that protecting vessels through high insurance premiums, onboard guards and re-routing costs $7 billion in comparison to the $160 million Somali pirates receive in ransoms or the comparatively small $16.4 million spent on prosecutions and imprisonment, there is an obvious disconnect and disproportionality in dealing with this issue. There is an ever present argument that insurance companies, as well as Private Maritime Security Contractors (PMSCs), earn more from piracy than the pirates themselves, which is well supported by this report, which showed evidence that 99% of piracy costs are recurring. This means that they will be repeated every year and will only fluctuate if piracy itself reduces to the extent that it warrants a change in political and economic approaches to the problem.

The report therefore suggests that stakeholders need to reassess the long-term sustainability of the costs outlined. The fear and preventative economic investment in piracy however looks set to increase with incidents such as Somali pirates launching their first attack in territorial waters when they raised a vessel near the Gulf State of Oman. One particularly disturbing piracy trend is that pirates have begun to focus their attention on people rather than ships. There have been incidents where pirates release the ships, but keep the crew for ransom purposes. This has extended to pirates kidnapping hostages on land such as humanitarian aid workers and tourists in Kenya and Somalia.

While not quantifiable in economic terms, the human cost of piracy is higher than any economic figure given. Twenty four people were killed by pirates in 2011, but hostages were held for longer in order to negotiate higher ransoms, which the report states took an average of 178 days (or six months). Also forgotten are the deaths of the pirates themselves. Due to the economic disconnect between pirate ransoms and the overall economic cost of pirate deterrence, it is clear that a purely mitigating or preventative policy does not offer a solution to control or alleviate piracy. Neither the military nor shipping industry have been successful in stemming the problems and the more money that is invested does not seem to reduce the cost to human life. One option is to stabilise the situation on the ground in Somalia in political and economic terms. As the report notes, very little is spent on the root causes of piracy, suggesting a redirection of investments from short-term symptoms to long-term solutions.

It is problematic to fully assess the legal framework in which the patrols could be deemed to operate as well as their relation with anti-piracy and armed robbery efforts. Interestingly, a cursory review of the history of piracy reveals limited reported instances of so called “

It is problematic to fully assess the legal framework in which the patrols could be deemed to operate as well as their relation with anti-piracy and armed robbery efforts. Interestingly, a cursory review of the history of piracy reveals limited reported instances of so called “