September 3, 2012

by Matteo Crippa

This time last year, we dedicated a few posts to the rise of piracy and other criminal activities in the Gulf of Guinea. In particular, we discussed how much of these activities was a by-product of internal insurgencies and economic discontent in Nigeria and how the country’s attempted crackdown had the unintended consequence of pushing these criminal activities to nearby countries where lack of enforcement powers allowed them to thrive.

The situation has since continued to worsen. While there is currently a lull in piracy activities in Somalia and the Gulf of Aden, armed robberies and pirate attacks are sharply on the rise in West Africa. Reported incidents in the territorial waters of Nigeria, as well as Togo and Ghana, or in the international waters adjacent thereto, are now almost a daily occurrence. In the most recent of such attacks, the MT Energy Centurion, a Greek-owned oil tanker was hijacked and its 24 member crew kidnapped off the coast of Togo.

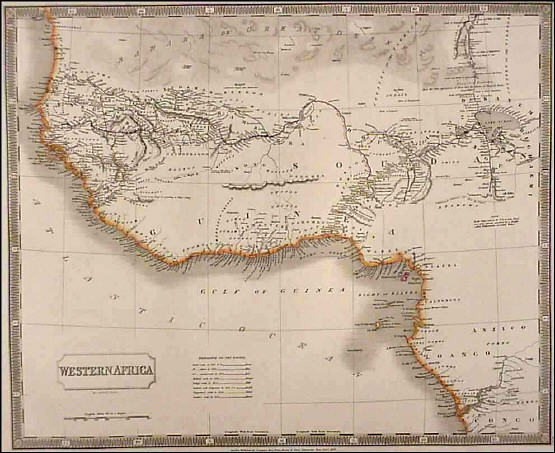

Historic Map of West Africa dated 1829 by Sidney Hall – Garwood & Voigt

The region is traditionally considered as a cornucopia of natural resources. West Africa is rich in oil and other hydrocarbons, but also fish, cocoa and timber, for instance. Nigeria is currently the biggest African oil producer, with an output of about 3 million barrels a day, most of which is exported to Europe and the US. Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone are the next countries to enter the oil production and export business, with new deposits discovered in their national waters in recent years. Such discoveries have the potential to bring economic development to some of the poorest countries in the world, in a region often forgotten even when plaugued by years of ruthless civil wars and rampant mismanagement. Development, however, needs to be matched by strong governance capabilities. Due to its social and geographical features, the Gulf of Guinea is not only suitable for commercial transportation but is also a potential hotspot for criminal activities, particularly exacerbated by unemployment, corruption and lack of governance. Oil bunkering, piracy, illegal waste dumping, poaching, drugs and migrant smuggling are only the most visible tip of a larger array of criminal activities. Autonomous movements also have increasingly resorted to violence, with terrorism often inexorably spurring into ties with criminality. These activities are often, but not exclusively, perpetrated by organized criminal cartels. Smaller criminal gangs, however, also operate some activities. Their common medium, often or exclusively, is the sea, which provides direct opportunities for criminal acts as well as the means to perpetrate such acts. Oil platforms in international waters are increasingly the targets of pirates and robbers, while subsidized petrol is smuggled from Nigeria into neighboring countries in overnight trips just a few miles off their coasts. Transmaritime criminality consists of the composite interaction of various forms of organized criminal activities, including criminal cartels, oil, drugs, arms and human trafficking, the deeply rooted social causes at their basis as well as their economic and environmental impact. Transmaritime Criminality thrives on the high seas as well as in coastal developing countries due to limited law enforcement and rule of law capabilities.

Despite its apparent similarities with pirate activities in Somalia, the situation in West Africa is potentially more complex. Attacks are often reckless, and more violent. Rarely do these entail long lasting hijackings and kidnapping for ransom. Presumably due to the lack of capabilities to hold a ship and its crew hostage for long periods, criminals often resort to stealing the ship’s cargo and releasing it after a few days. This was the case, for instance, in the hijacking of the MT Energy Centurion, which was quickly released in Nigerian waters with its crew after its valuable cargo was siphoned off. The oil will then likely be sold through the black market in face of the complacency, or powerlessness, of local authorities.

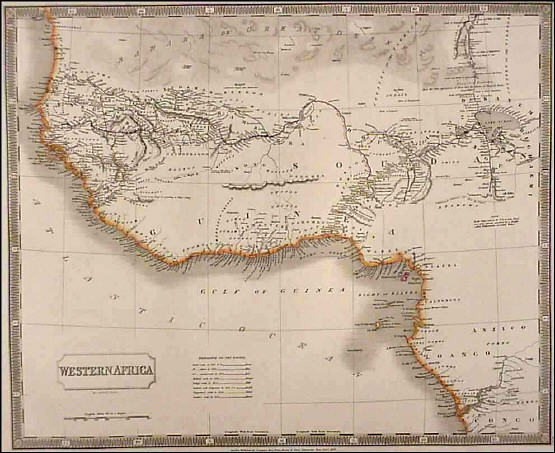

Subsidized Nigerian Oil is Smuggled Overnight to Togo and Picked up Directly Ashore to be Sold in the Local Black Market – Photo Daniel Hayduk – BBC

This criminal surge in West Africa did not go unnoticed at both the international and regional level. The UN Security Council has already dedicated various meetings and resolutions to the situation in the Gulf of Guinea. The US, but also France and China, among others, have stepped forward to provide assistance, in the form of training or equipment, to countries in the region. These, in turn, have engaged in coordination and dialogue, launching joint policing operations. The past spiraling of piracy in Somalia has obviously provided an indicator of the potential gravity of piracy thriving in lawless environments. It also developed a set of best practices in combatting piracy and its root causes. No internationally-sponsored naval patrolling mission akin to those launched by the EU or NATO in the Indian Ocean is foreseen in West Africa. The envisaged solution is that of a funneling these best practices through regional coordination, encompassing strategies of short and long term period, rather than direct international intervention. These strategies include the strengthening of enforcement powers and ad-hoc legislation. Typically, several affected countries have found their penal codes to be lacking the full criminalization of piracy and terrorism. A UN-sponsored regional conference aiming to put this phenomenon high on the agenda has been long envisaged, but yet failed to materialize. Against this background, it is worth reiterating the need to avoid the immediate risk of resource fragmentation, with already a plethora of UN and regional agencies and organizations involved as stakeholders. The fight against transmaritime criminality in West Africa has also the potential risk of becoming another lucrative self-feeding business, with military contracts already allegedly awarded to contractors of dubious background.