What Does Piracy Have to Do with North Korea?

May 21, 2012 1 Comment

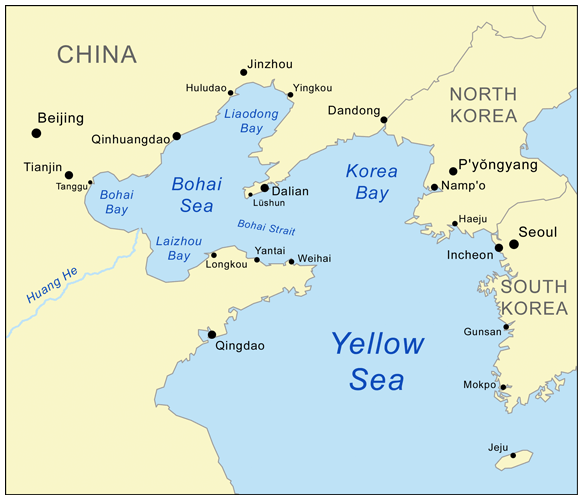

The reclusive authoritarian Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is once again back on the news headlines. Surprisingly, this time is not about the reactivation of its purported nuclear programme, or because of a new attempt to lift off a satellite/ballistic missile, or for some leaked information on the poor living conditions endured by its citizens. Media outlets are reporting on the possible hijack of 3 Chinese fishing vessels and the kidnap of their 29 crew members earlier this month. The vessels and all the captives were released today, following the intervention of the Chinese authorities. The incident has all the hallmarks of a piracy attack off the coast of Somalia or in West Africa. However, it occurred in the Yellow Sea, in an area between North Korea and China.

The reclusive authoritarian Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is once again back on the news headlines. Surprisingly, this time is not about the reactivation of its purported nuclear programme, or because of a new attempt to lift off a satellite/ballistic missile, or for some leaked information on the poor living conditions endured by its citizens. Media outlets are reporting on the possible hijack of 3 Chinese fishing vessels and the kidnap of their 29 crew members earlier this month. The vessels and all the captives were released today, following the intervention of the Chinese authorities. The incident has all the hallmarks of a piracy attack off the coast of Somalia or in West Africa. However, it occurred in the Yellow Sea, in an area between North Korea and China.

News reports are still contradictory and any in-depth analysis into this will necessarily depend on the real circumstances of the case. Notably, the incident has not been reported to the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre. In particular, it is not clear whether the incident took place in international waters. The identity of the assailants is also unclear. Some reports indicate that these were members of the North Korean military, while according to others Chinese mafia from the city of Dandong, on the North Korean border, might have been involved, possibly in cooperation with the North Korean military. Several news reports indicate that the vessels, originating from the city of Dalian, were accosted at sea by armed men and forced to sail to North Korea. The ship owners confirmed the capture of the vessels and their crew. According to the owners, the vessels were navigating within Chinese national waters. They also confirmed that the captors have asked for the payment of a ransom of nearly 190.000 US Dollars and have threatened to harm their captives if no payment was made.

If the assailants have no connection with state authorities, the main issue will be to determine whether the incident qualifies as piracy committed in the high seas rather than armed robbery within China’s territorial sea. However, whether the assailants are members of the North Korean military or not, the use of force and the request for a ransom renders them de facto pirates, because they appear to have acted in pursuit of private ends. If the available information is correct, their actions could also qualify as mutiny. In this regard, it is worth recalling that Article 102 UNCLOS encompasses acts of piracy committed by a government ship whose crew has mutinied.

Actions by the North Korea authorities have in the past drawn widespread international condemnation. However, it is difficult to envisage Pyongyang secretive rulers now embracing a state policy to terrorize fishermen in the Yellow Sea for ransom purposes, particularly when this has an impact on a longtime ally and regional military superpower as China. This latter routinely issues strong protests over fishing related disputes with Japanese, South Korean, Vietnamese or Philippine fishing vessels. China will likely take certain actions to prevent any further escalation of such attacks in the Yellow Sea, as it has done by policing Southeast Asia’s Mekong river from drug smugglers and criminal cartels. However, doubts remain on whether the public outcry sparked by this incident will have an impact on its already strained relationship with North Korea.