Last month, Mauritius became the latest country in the Indian Ocean area to enter into an agreement with the United Kingdom for the transfer of suspected pirates before its courts for prosecution. The agreement was announced earlier this year during the London Conference on Somalia, which highligthed the UK driving role in Somalia’s recovery, including the fight against piracy. Mauritius thus follows in the footsteps of Tanzania and the Seychelles who have recently penned similar agreements with the UK, in 2012 and 2010, respectively, aiming to break the pirates business circle by providing a jurisdictional basis for their prosecution after apprehension at sea.

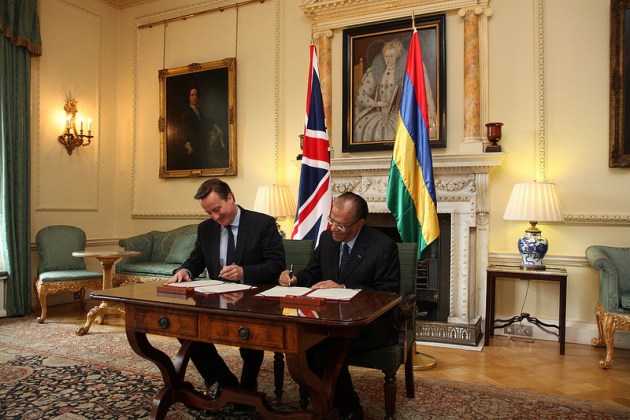

Prime Minister David Cameron and his Mauritius counterpart Navinchandra Ramgoolam sign the prisoners transfer agreement – FCO

Notoriously, foreign navies deployed off the Somali coast to counter piracy are reluctant to take pirate suspects to their own countries because they either lack the jurisdiction to put them on trial, or fear that the pirates may seek asylum. Evidentiary hurdles are also seen as an increasing impediment to effective prosecutions. Suspected pirates detained on the high seas are therefore often released after a brief detention due to the governments’ reluctance to bring them to trial.

Under the terms of the new international agreement, Mauritius will receive and try suspected pirates captured by British Forces patrolling the Indian Ocean. Last year, Mauritius entered into another agreement with the European Union for the transfer, trial and detention of suspected pirates captured by the EUNAVFOR naval mission. As reported on this blog, Mauritius has also inked a deal with the TFG, Somaliland and Puntland to start to transfer convicted pirates to Somali prisons, paving the way for the commencement of prosecutions in Mauritius.

The first trial of a suspected Somali pirates is due to commence in September 2012. In the meantime, Mauritius, already a signatory of UNCLOS, further strengthened its anti-piracy capabilities by adopting various relevant legislative instruments. First and foremost, a new anti piracy law was adopted at the end of 2011. The new Piracy and Maritime Violence Act 2011, premised on the transnational dimension of modern day piracy and the principle of universal jurisdiction to counter it, incorporates nearly verbatim in the national judicial system the definition of piracy as contained in Article 101 of UNCLOS. Acts of violence within Mauritius internal waters are defined as “Maritime Attack”. The novel term adds a degree of fragmentation in the definition of this offence, which is otherwise commonly referred to internationally as “armed robbery at sea”. In an attempt to cater for a wider range of piracy related criminal activities, the Piracy Act also criminalizes the offences of hijacking and destroying ships as well as endangering the safety of navigation. For each of these offences, the Piracy Act provides for a maximum term of imprisonment of 60 years.

More interestingly, the Piracy Act introduces the possibility for the holding of video-link testimonies and/or the admission of evidence in written form where the presence of a witness, for instance a seafearer, cannot be secured. While not uncommon in certain national criminal jurisdictions, as well as those of international criminal courts, the introduction of out of court statements, particularly when relevant to the acts and conducts of an accused, could trigger fair trial rights issues. These issues are principally due to the limited ability of the defence to test such evidence when relied upon at trial in the absence of the witness. In light of these concerns, the Piracy Act provides for the admissibility of evidence in rebuttal as well as for the court’s discretionary power in assessing the weight to be given to written statements.

In addition to the Piracy Act, which entered into force on 1 June 2012, Mauritius also adopted and/or amended its laws concerning assets recovery and mutual assistance in criminal matters in order to foster cooperation with foreign governments to tackle pirates and criminal cartels. The implementation of the agreement with the UK, however, is still to be fully tested. In May 2012, the UK announced that defence budget cuts required it to scale back its naval commitments in the region, withdrawning its ships from full-time counter-piracy operations.

The HMS Ocean Arrives in London Ahead of the London 2012 Olympic Games – Courtesy AP

These difficulties have been compounded by the need to commit ships and personnel to the security efforts for the London 2012 Olympic Games. The UK long-term commitment to combat piracy in Somalia extends beyond its current patrolling and disruption efforts in the Indian Ocean. To remain within the Olympic spirit, French Baron Pierre de Coubertin, considered the founder of the modern Olympics Games, famously noted how “The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.” With piracy attacks in the region at their lowest level, during monsoon season, however, it is worth considering whether we should be content with the current efforts to combat piracy, or whether we should be aiming for more.