Lockerbie in Arusha – Significant Challenges Remain

January 25, 2011 Leave a comment

UPDATE: Lang actually recommended the creation of three courts: one in Puntland, one in Somaliland, and one in Arusha (to be moved to Mogadishu when conditions warrant). The Security Council members are generally in support of his recommendations, but you can discern some variations in their preferences by parsing the language of their statements. A number of questions come immediately to mind: (1) how will an arresting force determine to which of the three courts to send an arrested person? (2) Have Puntland and Somaliland delimited territorial waters where they would have exclusive jurisdiction? (3) Insofar as any nation may prosecute piracy on the High Seas, will the process of determining the proper venue be ad hoc or based upon formalized negotiations and agreements?

Jack Lang, UN Special Adviser on Piracy, has issued his report to the Secretary General. News agencies are saying that he has recommended the creation of a Somali court sitting in another regional state (akin to the Lockerbie court). There is some indication that Arusha, Tanzania is being considered as a seat for the Somali court due to the infrastructure already in place at the ICTR. A number of serious challenges would need to be overcome to create such a court.

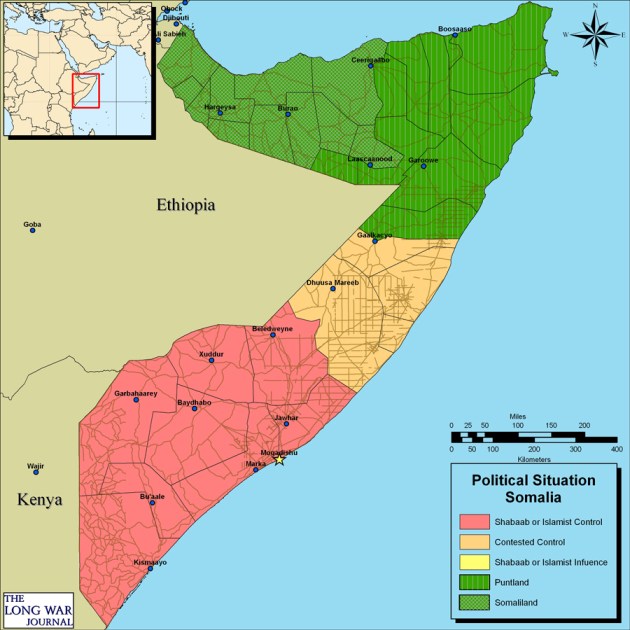

First, Somalia continues to be described as a monolithic entity, thereby necessitating a bilateral treaty between the regional State in which the court would be situated and Somali. However, the United States policy has recently changed with regard to the heretofore unrecognized regions of Somaliland and Puntland. Assistant Secretary of State Johnnie Carson said at a briefing in September 2010:

We hope to be able to have more American diplomats and aid workers going into those countries [Somaliland and Puntland] on an ad hoc basis to meet with government officials to see how we can help them improve their capacity to provide services to their people, seeing whether there are development assistance projects that we can work with them on […] We think that both of these parts of Somalia have been zones of relative political and civil stability, and we think they will, in fact, be a bulwark against extremism and radicalism that might emerge from the South.

Carson said the United States will follow the African Union position and recognize only a single Somali state. However, with Somaliland and Puntland apparently offering to house convicted pirates within their territories, and other States increasingly recognizing their practical autonomy, it begs the question of whether or not an agreement to create a Somali court would require the assent of the Somaliland and Puntland governments. It would seem that a prerequisite to these regions signing an international treaty would be recognition of their Statehood.

The 26 July 2010 Report to the Security Council set forth several additional challenges with regard to the option put forward by Lang. These include:(1) the considerable assistance that the UN will need to extend to the court; (2) the amount of time necessary for the court to commence functioning could be significant; and (3) the inadequacy of Somalia’s piracy laws and the capacity of Somalia’s judicial system. In particular, the report noted:

Although there is some judicial capacity in Somalia and among the Somali diaspora, the challenge of establishing a Somali court meeting international standards in a third State would be considerable at present. Further, any advantages that such a court may enjoy would be outweighed if it were to draw limited judicial resources from Somalia’s courts.

One final point that should not be lost amidst the excitement is the mundane, but essential task of determining where Somalis who are eventually convicted of piracy, in the yet to be created court, will serve their sentences. Apparently, Lang has recommended the construction of one prison each in Somaliland and Puntland. To which, Bronwyn Bruton, an author of reports on Somalia for the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations, reportedly said:

The idea that they’re [pirates] going to be scared off by prisons that meet UN human rights standards is wholly unrealistic. In these jails, they will have food, protection from violence and probably some basic literacy training. For these guys, it’s going to sound like a holiday camp.

Indeed the prospect of serving time in these prisons may not create a serious deterrent to piracy. However, during the 8 or 20 years in which a pirate might serve a sentence, he will not be capable of committing further acts of piracy. Furthermore, rehabilitation is a real possibility if stability can be maintained, jobs created, and inmates trained. Any sustainable solution should take into account the possibilities for a newly released pirate. If it does not, there is nothing to stop a jobless, ex-convict from continuing to seek bounty on the high seas.