A South Korean Navy-issued photo shows SEAL troops storming the Samho Jewelry hijacked by Somali pirates in the Indian Ocean

UPDATE: The question has been raised in another forum how acts of piratical torture might be imputed to a State authority (as CAT is only applicable where such authorities participate in or acquiesce to such conduct). There are at least two cases on point. In 1999, the Committee Against Torture held that factions within Somalia “exercise certain prerogatives that are comparable to those normally exercised by legitimate governments,” and therefore, “the members of those factions can fall, for the purposes of the application of the Convention, within the phrase “public officials or other persons acting in an official capacity” contained in article 1 [of CAT]”. See Zelmi v. Australia. Similarly, a UK criminal court has held that an Afghan warlord could be considered a de facto public official for purposes of CAT even though a central government existed in Afghanistan at the time. See R v. Zardad. The crucial issues in that inquiry were: (1) the degree of organization of the entity; (2) the level of control exercised over a region; and (3) whether the entity exercised the types of functions that would normally be exercised by a government.

Since a majority of pirate attacks originate in the unrecognized region of Puntland, the question then becomes whether the officials in Puntland are to be held responsible as de facto public officials, or even, whether the leaders of pirate enterprises might be considered de facto public officials if they exercise effective control over the towns or regions in which they reside. The existence of a Transitional Authority in Mogadishu does not seem to prevent application of CAT since it does not have any influence outside a small part of the capital.

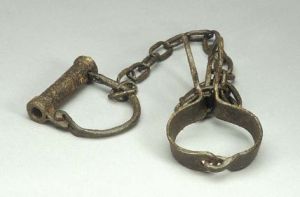

So much for pragmatic businessmen. Escalation is the word of the day. A seamen on a ship captured off of the Seychelles was killed, apparently in retribution for an attempted rescue. In another report, South Korean seamen from the Samho Jewelry described how their Somali pirate captors beat them. A Major General explained that Somali pirates “have begun systematically using hostages as human shields and torturing them.” These reports raise an important legal question: can the Somali pirates who hijacked the Samho Jewelry and who are currently being detained in South Korea, be prosecuted for torture?

There are at least two legal issues here: one jurisdictional and the other substantive. As to the first issue, the UN Convention Against Torture (UNCAT) provides that a State may exercise jurisdiction to prosecute a suspect for torture: (1) where the offence took place in its territorial jurisdiction or onboard a ship registered in that State; (2) where the suspect is a national of that State; or (3) where a victim is a national of that State. See UNCAT Article 5(1). Even where none of these criteria are met, UNCAT also permits any State in which the suspect is present to exercise jurisdiction. This begs the question, how a suspect would find himself in a State which did not, but for his presence, have jurisdiction to try him. Of course, once the suspect is transferred to any State, his presence alone would grant that State jurisdiction to try him on torture charges. But what is the legal basis for arresting and/or extraditing the suspect on torture charges, if none of the four jurisdictional criteria are met prior to the extradition?

In any event, the alleged victim appears to be a South Korean national. Therefore, there is a basis for exercising jurisdiction pursuant to UNCAT. Note: the Samho Jewelry is a Maltese flagged ship, so Malta would also have jurisdiction.

As to the second legal issue, the definition of UNCAT creates a problem in the prosecution of non-state actors. UNCAT was devised to prohibit torture by States and defines torture as:

Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person [to obtain information, as punishment, intimidation, or coercion or for any discriminatory reason], when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. (emphasis added).

Therefore, one element of the offence of torture pursuant to UNCAT is the participation of a public official. In a failed State such as Somalia, there are no public officials or other persons acting in any official capacity to consent or acquiesce to the conduct. This element cannot be proven and a prosecution for torture would fail.

The ICTY Appeals Chamber has addressed the peculiarity of the public official requirement in the UNCAT definition of torture. In one case, it held that the definition of torture in UNCAT, which now constitutes customary international law, included a public official element. See Furundzija Appeal Judgement at. para. 111. But in a subsequent case, in dicta, the ICTY Appeals Chamber opined, “[t]he public official requirement is not a requirement under customary international law in relation to the criminal responsibility of an individual for torture outside of the framework of the Torture Convention.” See Kunarac Appeal Judgement at paras. 147-48. In other words, where a State is concerned, there is a public official requirement. But where a State is not involved, the crime of torture does not require the involvement of a public official. Considering this was dicta, the issue has not been definitively resolved.

South Korea ratified UNCAT in 1995, but whether or not it could prosecute Somali pirates for torture would depend on the domestic legislation that was passed in conjunction with its ratification. If South Korea’s domestic legislation incorporated the public official requirement in the definition of torture, it might create a barrier to prosecution on this charge.

I should note that Piracy is defined by UNCLOS as “any illegal acts of violence,” and therefore, encompasses within its broad definition, acts of torture. See UNCLOS Article 101(a). However, there may be circumstances where a prosecution for Piracy fails and reliance must be made on other charges. In such a situation, UNCAT would provide a novel basis for prosecution.